-

Matsuyama spoke to us about his inspiration behind 'Portraits of Dazzle':the deceptive allure found in social media and WWI Dazzle camouflage.

What first compelled you to incorporate dazzle camouflage into your work?

I became interested in the striking appearance and narrative of Dazzle camouflage after watching a documentary about World War I. In today's society, where communication revolves around social media, it's crucial to share visually appealing information to fulfill the desire for approval through likes and follower counts. This includes using filters to enhance skin appearance, portray a slim figure, remove unnecessary elements from images, or transform cloudy skies into clear ones. The deceptive allure of posts that appear beautiful on social media, much like how Dazzle camouflage deceived enemy ships, aligns perfectly with the theme of my artwork. That's why I incorporate Dazzle camouflage as a motif in various pieces.

Dazzle camouflage was used to intentionally mislead enemies. How do you find this captures what you’re trying to explore through your portraits?

I am a contemporary artist, but in my work "Portrait of Dazzle," I play the role of both a portrait painter and a viewer of social media. In traditional portrait painting, artists and models typically interact face-to-face to complete the portrait. However, in my work "Portrait of Dazzle," the artist paints the model (a selfie on social media) through a smartphone screen. During this process, the artist and model have no personal acquaintance, and the model may not even be aware they are being depicted. This production process reflects modern communication methods.

Your practice centres around the concept of ‘modern people’ often concerned with self-image. What drew you to explore this theme in such detail?

With the widespread adoption of the internet and smartphones, our society is undergoing unprecedented changes at a pace never before experienced by humanity. I am intrigued by what "modern people" are exposed to, what they think about, and how they are evolving.

How does your background in illustration inform your practice, if at all?

My background in illustration informs my artistic practice by approaching my work not just sensually, but also rationally and theoretically. I bring a marketing perspective gained from my experience as an illustrator and designer to my activities as an artist.

You’ve recently been working on objects and installations. Do you feel this was a natural progression?

I have been creating installation artworks since around 2015, up until the early stages of the pandemic. After the pandemic made attracting audiences challenging, I began considering creating paintings that could be appreciated and purchased online, which led to the completion of "Portrait of Dazzle.”

To enquire about available work please click here

-

We had the pleasure of asking Yohta Matsuoka a few questions about his journey as a street artist and as a painter, and understand his concept of 'Sincerity' when it comes to bridging seemingly polar opposite elements on canvas.

Questions of perspective are at the centre of your work. What message are you trying to express through your compositions?

I believe that even the most mundane objects and familiar sights, like the apples frequently featured in my work, can appear different when viewed from another angle. I try to convey this by manipulating the composition of my artwork. From a broader perspective, it's about not taking things for granted and recognising that even on the most routine days, no two days are the same.

Your work makes interesting use of colour and pattern. What informs your choices when conceptualising a new piece?

The most crucial factor when creating a new piece is whether or not I feel compelled to paint it. I also ask myself if there is a compelling narrative or concept within the world I am trying to depict.

Having produced work both in the streets and on canvas, can you walk us through your creative process for each?

I haven't been as active on the streets lately! But every now and then, I might put up a sticker, or if I have a pen in my pocket, I might impulsively scribble down a thought. Or maybe just my tag. It's all about impulse and timing. Canvas work, on the other hand, is much more deliberate. First, I sketch on my iPad, digitally collaging the composition, colours, and various objects to create the image. Then I give it some time. Sometimes I notice things that bother me the next day. Once I've decided on a sketch I want to paint, it's like replicating the digital sketch onto the canvas.

Your mural work differs slightly to your work for galleries. What drew you to begin creating these slightly abstract still-life paintings?

I started this series when COVID hit and the lockdowns began. People's activities came to a halt, the city was drained of its vibrancy and people, and it felt like I was looking at a monochrome, still world. As a painter, I felt compelled to react to this unusual world, and I started by placing simple objects on a blank, monochrome canvas. Like restarting a world that had been reset. In doing so, I realised that by carefully arranging recognisable, everyday objects, I could create faces. I realised that they were both still lifes and portraits. Then, with the hope that the abnormal situation caused by COVID would eventually end, I set the time of day to be before dawn, when the sun would rise and night would turn to day. It's monochrome, dark, and unsettling, but the faces that emerge are smiling and seem to harbour positive elements.

‘Sincerity’ explores the dichotomy between classical and contemporary art. How does this reflect your artistic vision?

For the past few years, I have been painting still lifes, which could be considered a fundamental expression of art. They provide an excellent opportunity to study the characteristics of each object, such as its shape and colour, through my brushstrokes, leaving me feeling calm and serene. At the same time, I am drawn to graffiti art and urban culture, which excite me and make me feel incredibly energised. I believe that the fusion of these seemingly polar opposite elements within me represents who I am - a quiet and calm individual with a curious and active mind. By honestly embracing both aspects, I feel a sense of balance. And I believe that it is through a sincere confrontation with the canvas during the painting process that my vision emerges.

To enquire about available work please click here

-

WE TOOK THE OPPORTUNITY TO ASK add fuel A FEW QUESTIONS ABOUT HIS WORKING PRACTICE AND NEW BODY OF WORK 'simply squares'

Azulejo tiles have long been an important medium for creative expression, often chronicling major historical and cultural events. What first drew you to using them in your designs? What is the significance of re-appropriating traditional crafts?

I was first drawn to the usage of the azulejo back in 2009 when I received an invite to participate in a project in my hometown of Cascais. I felt that I needed to create an artwork that would represent the heritage of this village city 650 years of history. The idea rapidly grew into something larger than just utilising the aesthetic of tiles, it became, for me, a way to express myself through the language of my ancestors, I wouldn’t say through re-appropriating, but through re-creating and re-inventing this language.

Is there a central idea you want to express through juxtaposing the aesthetics of traditional tile work with the contemporary influences that are revealed upon closer inspection?

Yes. I felt that it’s important to look to the past, remember our roots and our traditions, while having an eye in the present and in the future while looking into how we can envision art as a medium that communicates through time itself.

‘Each square harbours a story waiting to be unearthed.’ How do you decide what stories you want to tell and what characters to incorporate?

I have a very intuitive and visceral process of drawing, sometimes these stories, elements and characters are planned and I want to transmit a specific idea, but most of the times I let my hand roam free while drawing and see how the drawing itself evolves.

Your compositions are complexly layered and repetitive, often featuring rips. How do you feel this reflects on cultural identity and urban landscapes?

Working with squares has always been my challenge and specifically finding ways to disrupt the rigidity of the shape itself. The rips and layering effect allow exactly that rupture, allow the requires space for dynamism to happen. The layering effect can and has also been interpreted as a sort of peeling the layers of time, if this makes sense, allowing for the different squares to exist in the same space but in different eras.

Was it a natural progression to begin creating works on walls and in the streets?Yes it was. I started creating studio work first with the tiles. I wanted to solidify the structure of my work with the tile aesthetic, but the step to move them to the streets was quite natural. In Portugal is quite common to have building facades covered in tiles, so for me it was a natural step to take my work into the streets. I first started with very small tile pieces, but rapidly moved into stencil (and freehand spray) based murals.What does your creative process typically look like?I start with a sketch, always. This sketch, as I mentioned earlier, can be based on telling a story or just an intuitive drawing. On a second step this sketch moves to fine lining and color. From here, the artwork might go into a tile, might be adapted to a stencil, might be hand painted in a larger mural or go into a screen print. And it is usually combined with other patterns in dynamic compositions.

Was it a natural progression to begin creating works on walls and in the streets?Yes it was. I started creating studio work first with the tiles. I wanted to solidify the structure of my work with the tile aesthetic, but the step to move them to the streets was quite natural. In Portugal is quite common to have building facades covered in tiles, so for me it was a natural step to take my work into the streets. I first started with very small tile pieces, but rapidly moved into stencil (and freehand spray) based murals.What does your creative process typically look like?I start with a sketch, always. This sketch, as I mentioned earlier, can be based on telling a story or just an intuitive drawing. On a second step this sketch moves to fine lining and color. From here, the artwork might go into a tile, might be adapted to a stencil, might be hand painted in a larger mural or go into a screen print. And it is usually combined with other patterns in dynamic compositions. A lot of your murals are site-specific. How much time do you spend researching before conceptualising each piece?Correct, they are. I felt that a mural should be part of the neighbourhood or city/country where it is located, so yes I do quite a lot of research. I do a lot of online research for patterns associated with that location, either tile patterns, fabric or even architectural elements and most of the times I talk to local people that can point me in the right direction.You’ve mastered a lot of techniques - graphic design, illustration, ceramics, stencils - is there anything new you’ve been exploring, or would like to in the future?I have a very curious mind by nature and I try to keep my horizons open. Most recently, in the past 3 or 4 years I’ve been including a lot more freehand spray painting in my murals as I feel that this contributes to the richness of the composition of the murals. In the studio we have been doing some interesting partnerships with tile factories also to explore new techniques.

A lot of your murals are site-specific. How much time do you spend researching before conceptualising each piece?Correct, they are. I felt that a mural should be part of the neighbourhood or city/country where it is located, so yes I do quite a lot of research. I do a lot of online research for patterns associated with that location, either tile patterns, fabric or even architectural elements and most of the times I talk to local people that can point me in the right direction.You’ve mastered a lot of techniques - graphic design, illustration, ceramics, stencils - is there anything new you’ve been exploring, or would like to in the future?I have a very curious mind by nature and I try to keep my horizons open. Most recently, in the past 3 or 4 years I’ve been including a lot more freehand spray painting in my murals as I feel that this contributes to the richness of the composition of the murals. In the studio we have been doing some interesting partnerships with tile factories also to explore new techniques. What made you choose the moniker you work under, Add Fuel (To The Fire)?I initially used Add Fuel To The Fire, yes. I always like that expression, not by its negative meaning, but because in my mind, my work would be the fuel that would ignite something in the art world. I then shortened to ADD FUEL simply by aesthetic reasons, it’s shorter, easier to remember. It lost a bit of the original meaning, but I believe now it also gained new meanings, different meanings open to interpretation.You’ve previously shared how collaborating with other artists forces you to think in a different way. What was it like working with D*Face to create an edition for this show?I do love to collaborate with other artists, I feel that both works become something more when combined in the best way possible and I’ve been a fan of D*Face’s work for quite a long time so the combination was quite easy to achieve. I quite enjoy the boldness of his work, the big strong elements, and this was crucial for this collaboration, combining the bold and strong with the detailed and intricate of my patterns.

What made you choose the moniker you work under, Add Fuel (To The Fire)?I initially used Add Fuel To The Fire, yes. I always like that expression, not by its negative meaning, but because in my mind, my work would be the fuel that would ignite something in the art world. I then shortened to ADD FUEL simply by aesthetic reasons, it’s shorter, easier to remember. It lost a bit of the original meaning, but I believe now it also gained new meanings, different meanings open to interpretation.You’ve previously shared how collaborating with other artists forces you to think in a different way. What was it like working with D*Face to create an edition for this show?I do love to collaborate with other artists, I feel that both works become something more when combined in the best way possible and I’ve been a fan of D*Face’s work for quite a long time so the combination was quite easy to achieve. I quite enjoy the boldness of his work, the big strong elements, and this was crucial for this collaboration, combining the bold and strong with the detailed and intricate of my patterns.Enquire here to request details of available works by ADD FUEL

-

Last fall Scott Listfield and his brother took a trip to step into their ancestor's footsteps. Each painting in this show is from a stop along the way.

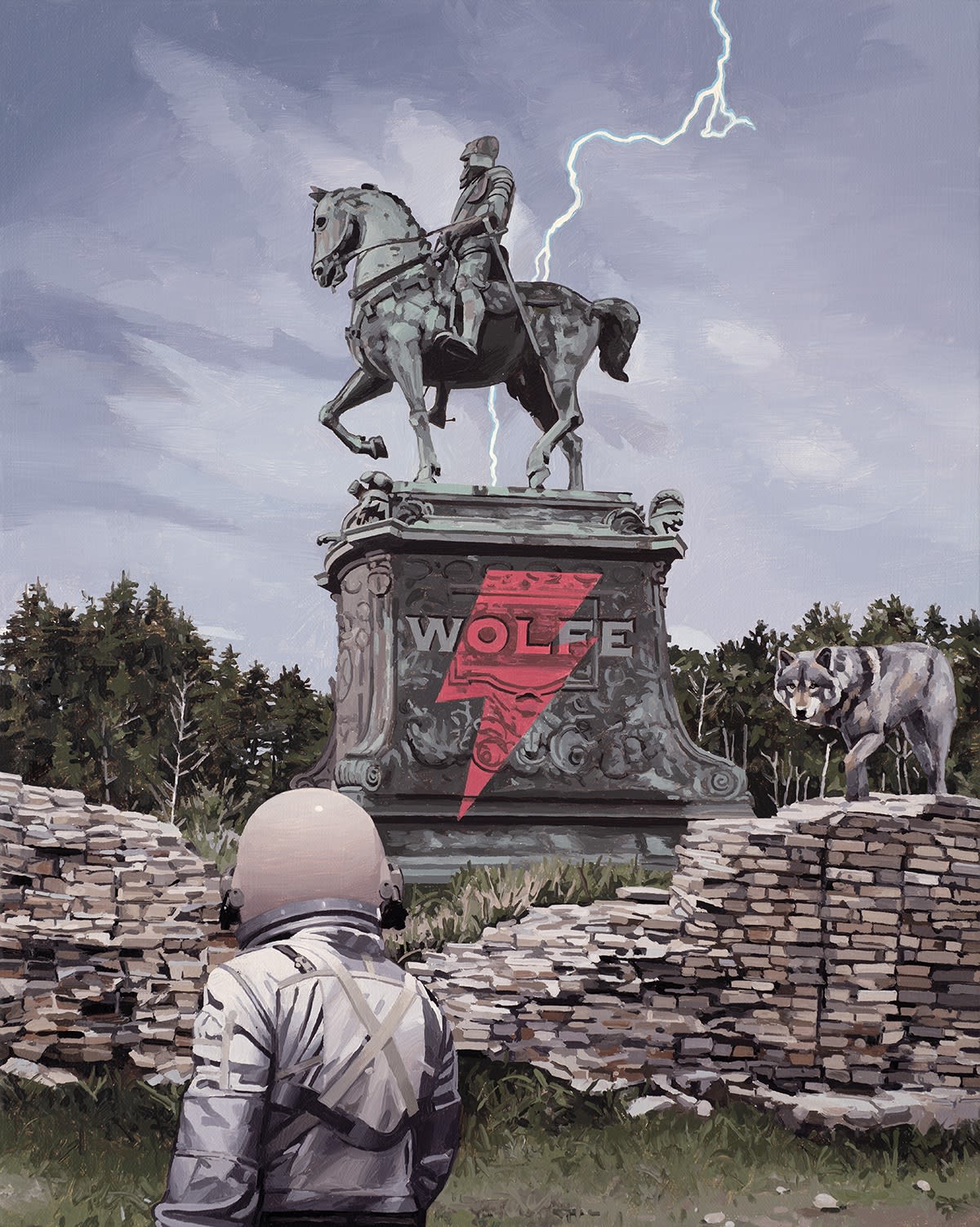

The Equinox

Here's a story about a wolf.It begins a long time ago when a much younger version of me went off to Europe for the first time. I studied in Italy. I walked cobblestone streets. So many cobblestone streets. I rode trains and saw places I might never see again. I came home and those journeys eventually inspired me to paint astronauts.Last fall I traveled to Europe again. From Oslo I flew to Riga, Latvia and met up with my brother at the airport, who had arrived just before me from Boston. We spent the next week traveling through Latvia and Lithuania to the places where our ancestors once lived. I didn't really have any preconceived notions as to how this part of the trip would go. There would probably be no long lost Listfield cousins to find. No one in my family is left in this part of the world. I guess I wanted to see where I come from. I wanted to walk the same cobblestone streets my ancestors once did. I didn't expect anything profound to happen. It did though.Our trip ended in Vilnius, Lithuania's very charming capital city. Arriving late, and tired from the road, we wound up by chance walking along the river that winds its way through the center of town. The sun was setting, and it was a mild September night. People were about. Lots of people. So very many people. My brother noticed it first: something was happening. That's when we saw the wolf.On the riverbank just ahead of us was a large statue of a wolf. Looming over it was an ancient castle tower, lit dramatically from below and perched precariously on a hill. As the last bit of sunlight faded, the wolf spoke.I don’t speak Lithuanian, but some quick googling revealed that the wolf was sharing the story of the founding of Vilnius. It spoke in a booming voice, with occasional pauses as music swelled. Fire from an unknown source danced around the bottom of the wolf and eventually, as the night wore on, it was engulfed in flames. Smoke and hot ash fell on our faces. I wondered if we were a safe enough distance away.As the fire subsumed, we wandered off, dazed, along the river bank with hundreds of Vilnius residents. We had just celebrated the fall equinox and the 700th anniversary of the founding of Vilnius. It felt like we had just been part of something very primeval. I felt Lithuanian. I felt pagan. I felt wolf. I returned to my hotel room, ash still on my face.Epilogue: My third great grandfather was born in the small town of Šėta, Lithuania, sometime around the year 1837. His name was Wolfe.

The Wolf House

I arrived in Oslo knowing that the show I was supposed be having there had already been canceled. Something tragic had happened with the gallery curating the show, just a few days before I left for Scandinavia. It was too late to cancel my trip, and so I went anyways, trying not to let the sadness and suddenness of that tragedy hang over me while I traveled. But once I arrived in Oslo, the dark clouds and rain felt like a reminder. It was hard to shake the feeling of sadness hanging over both me and the city. But after a day in Oslo, I was joined by another artist who was supposed to be in the show. She too, had bought a plane ticket not knowing the whole thing would be called off, and so both of us, in town for no real purpose, wandered Oslo in the rain. We tentatively talked of the tragedy. She suggested we light a candle in one of the towering cathedrals in town. Despite neither of being particularly religious, I liked this idea. We stopped at a local bakery for a light lunch, and then took a corner and found ourselves facing a cobblestone street and a small, brightly painted house. I felt my spirits begin to lift and later that day the clouds began to break and we spotted the sun over Norway for the first time.

On The Island

I spent three days in Gothenburg, a truly lovely city with canals, street cars, and countless hills on Sweden's western coast. Carved out by glaciers and the sea, archipelagos dot the coastline, and on my last day there I hopped a train from the city center out to the town where the ferry departed. I spent the day alone, wandering the small villages, forests, and hills of those Swedish isles. In some ways it reminded me of visiting my grandparents when I was very young, who lived near the sea north of Boston, Massachusetts. In other ways it reminded me of no place I'd ever been before. Clouds rolled in and out over the rocky landscape, but it never rained and eventually the sun broke through and warmed me as I got lost in the forest, the high grass, and the many meandering inlets of the islands.

The Red House

On the island outside of Gothenburg, Sweden, I spotted a hill. Most of these islands are small and low lying, and the hills modest. But this one, carved from rock, pointing up from the sea, captivated me from as soon as I departed the ferry. I made a line for it and clambered up it's side. At the top was a tiny red house, more of a shack or a shed, really. I'm not sure what it's purpose was, whether it once operated as a lighthouse, or merely a one room place to lie down for a night and monitor the activity of the nearby islands. But when I crested the hill, I knew this was a place I'd remember forever. The clouds, a constant companion during my exploration of these small islands, had parted, drifting outward toward the horizon and letting the sun shine down. I looked out over the sea, across the numerous multicolored rooftops, and felt surprisingly at home in a place that also felt otherworldly. I let the sun warm me as I soaked in as much of the view as I could. The next morning I'd be leaving for Oslo. I might never make it back to this part of the world again, and I wanted to remember as much of it as I could.

The Archway

Perched high on a hill overlooking the old town in Gothenburg is a fortress. My first day there I climbed the hill, looking for the high ground to get views of the entire city. Gothenburg has countless hills and, to my delight, countless stairways leading up those hills. I spent the day climbing hills and visiting stone forts and wooden chapels, bridges over canals and streams and wandering through forested parks. This was still early in my trip and only in hindsight did I feel the presence of a wolf companion. I hadn't yet visited the places where my ancestors were from. But I felt like I was, in a way, retracing the steps of a much younger version of myself. Although I had never been to this part of the world before, I spent a formative part of my life traveling through Europe, largely on my own, and those travels shaped who I am and inspired me to make my very first paintings of astronauts. A lone traveler, lost in a world that is recognizable but not his own. History hangs over this place. It's not my history. But now that I've been there and seen it in person, it becomes part of my own story.

The Stairway

People who know me well know that my unusual pastime of choice is to walk stairs. I moved to Los Angeles from Boston around 5 years ago. When the pandemic hit, and I found myself locked in and bored, and I began walking the numerous stairs cut into the hills and mountains near my new home. When I arrived in Kaunas, Lithuania with my brother, after spending the previous days visiting smaller towns where our ancestors once lived, I was excited to find that Kaunas had hills and stairs of it's own. I spent our first night there tentatively exploring the ones nearest where we were staying, then my brother joined in the following morning as we explored the city from it's highest points, climbing hills to churches and monuments, statues and overlooks, occasionally hopping an ancient funicular along the way.

This particular stairway, captured that first night in town, was covered in graffiti and bright lights lit up the forest hanging above it. The wolf who appears in each painting in this show represents a few different things, but I think of it primarily as a ghost of my ancestors accompanying me on this trip where I visited the places they once lived. Vilkas means wolf in Lithuanian. And the names written on the wall are my direct patriarchal line. Listfield's starting with me and my brother, and going backwards – my father, my grandfather, my great-grandfather – all the way back in time, as far as I can trace. The ancestors who lived in this part of the world, those of us who had never been there, and then me and my brother, visiting for the first and maybe only time, to see the places where we come from.

The Wall

Unsurprisingly, when traveling through old European cities, I saw a lot of statues on this trip. Monuments to leaders long gone, kings and noblemen and warriors. A whole mythology to remember glorious achievements from the past. I also visited crumbling walls and overgrown sites of battles and massacres. Some were entirely unmarked. Left for nature to reclaim them. I visited places where distant family had been killed during various wars. Murdered for no real reason and tossed into a pit. These parts of my trip were sobering. In some of those places the memory burned bright. Statues and plaques and historical markers, so that no one would forget what had transpired. In other places there was less than nothing. Just roads to nowhere, overgrown forests, nothing at all to indicate the lives that had been fought for and lost in those places.I wanted to combine many of those things into one image in this painting. The crumbling walls, the statues, the forests and overgrown plots of land. I placed the name of my own ancestor on the statue. My third great grandfather's name was Wolfe. A coincidence I only realized later, after the wolf had already become the defining figure of this story. Wolfe led a modest life. He was a teacher in a small town in Lithuania. His son Chaim left for England, and a better life hopefully, and eventually he joined him there, in Leeds, where he passed in 1902. There is no monument to his struggle. I'm not sure there is even a gravestone. But here, in this painting, there is.

The Road

On the far outskirts of Kaunas, Lithuania is a place called the ninth fort. It was completed just before World War I and served as one of a series of defensive bastions for the city. When the Soviets swept in at the beginning of World War II, it became a jail for political prisoners. During the Nazi occupation later in the war it became a massacre site, mostly for the local Jewish population. I don't know if anyone in my family ended up there, but it's certainly possible. After the war, the Soviets reclaimed the site and erected a haunting monument to those lost in the Nazi massacre.This site was one of the more sobering stops on my trip, and yet I was captivated by the beauty of the monument itself. In this painting I've remade it, but placed it far from the manicured lawns and rolling hills of the site itself. The dusty road and high unkempt grass is from a different stop on our trip. Another massacre site. Another place my ancestors might have lived and might have died. This place was forgotten. No marker. No towering monument. Only forgotten memories. This trip, the good and the bad, the remembered and the forgotten, lies along that road. My brother and I followed it to wherever it went. We didn't know it at the time, but there was a wolf there, too. Sometimes it led and sometimes it followed. The wolf lived there, somewhere, along that road.

The Plaza

My trip wrapped up in Vilnius, Lithuania's stately capital city. Filled with towers and churches, monuments and plazas, my brother and I spent three days walking the city, coming to grips with the places we had seen on this trip. We had spent the previous week visiting smaller towns where our ancestors came from. In some of those places I felt the memory of that history, still alive and vibrant, despite there being no living members of my family still there. In other places, the history had been literally bulldozed. Empty fields and abandoned roads where people once lived and where people once died, overgrown cemeteries that in another generation or two will be lost forever. I felt caught between my own family history, the lives they lived, largely uncelebrated but key to my own existence, and the grandeur of monuments to cities and kings and saints. The two began to blend in my mind. This trip had been something like me creating a monument of my own to my past, my ancestry, to those who came from the small towns, to those who lived and dies, those who fled, and those who didn't make it out in time. There are monuments in my mind mind now also monuments in my paintings, to those people who came before me.

Enquire here to request details of available works by Scott

-

Whilst in London for his first show 'Tokyoverse' with StolenSpace, we took the opportunity to ask Geoffrey a few questions about his working practice and new body of work.

How has living and working in Japan influenced your life and artistic practice?I arrived in Japan when I was 21 years old. Since then, this country has deeply influenced my life and artistic practice. I have developed here, and the impact on my work is significant. I now consider myself more of a Japanese artist than French. My style is a blend of manga and the graphic style characteristic of contemporary Japanese painting. Takashi Murakami pioneered the "superflat" movement, where the painting is very flat, almost as if it were printed. My works exhibit this characteristic: they are very flat, without traces of brushstrokes. My black and white style also references manga pages, which are almost exclusively in black and white. What does your creative process look like when conceptualising new pieces?When I conceive a new piece, I primarily focus on the overall composition. Finding a delicate balance is essential, regardless of the subject matter. I always start with a quick sketch, which I then rework several times until I achieve the desired result. As my work is almost always in black and white, line prevails over color; that's the aspect I primarily focus on. Then, I adopt a very minimalist approach. I work in a restricted space, which forces me to use few materials. I only need a few brushes, my pot of black and white, and that's it!

What does your creative process look like when conceptualising new pieces?When I conceive a new piece, I primarily focus on the overall composition. Finding a delicate balance is essential, regardless of the subject matter. I always start with a quick sketch, which I then rework several times until I achieve the desired result. As my work is almost always in black and white, line prevails over color; that's the aspect I primarily focus on. Then, I adopt a very minimalist approach. I work in a restricted space, which forces me to use few materials. I only need a few brushes, my pot of black and white, and that's it! Who have been your biggest influences when developing your artistic language?This question is complex because I'm passionate about art and artists in general. I'm familiar with the biographies of artists, mainly from the 20th century. Therefore, they have all, in one way or another, influenced my work. Without going into too much detail, I can mention two who have particularly influenced my practice: Fernand Léger and Tomoo Gokita (one French and one Japanese!). Fernand Léger inspired me with the structured aspect of his forms and his "cylindrical" style, elements that are also present in my works. As for Tomoo Gokita, his strong use of contrast in his black and white paintings, as well as the way he manipulates light in his works, have been crucial aspects for me in my paintings in recent years.

Who have been your biggest influences when developing your artistic language?This question is complex because I'm passionate about art and artists in general. I'm familiar with the biographies of artists, mainly from the 20th century. Therefore, they have all, in one way or another, influenced my work. Without going into too much detail, I can mention two who have particularly influenced my practice: Fernand Léger and Tomoo Gokita (one French and one Japanese!). Fernand Léger inspired me with the structured aspect of his forms and his "cylindrical" style, elements that are also present in my works. As for Tomoo Gokita, his strong use of contrast in his black and white paintings, as well as the way he manipulates light in his works, have been crucial aspects for me in my paintings in recent years. For ‘Tokyoverse’ you aimed for a much more focused approach by removing context and backgrounds. What led you to this decision?I already partially answered this in the previous question, haha. However, there is another reason why I removed the background. Some time ago, my works were very complex, with very anarchic shapes where the subject often got lost in the background. It was difficult to distinguish the central character from the rest, which sometimes gave the impression of an abstract painting if one didn't pay attention. With "Tokyoverse," I am clearly paying homage to contemporary Japanese painting. I highlight female portraits in a clean and graphic style. So, I would conclude with the idea that "Less is More"

For ‘Tokyoverse’ you aimed for a much more focused approach by removing context and backgrounds. What led you to this decision?I already partially answered this in the previous question, haha. However, there is another reason why I removed the background. Some time ago, my works were very complex, with very anarchic shapes where the subject often got lost in the background. It was difficult to distinguish the central character from the rest, which sometimes gave the impression of an abstract painting if one didn't pay attention. With "Tokyoverse," I am clearly paying homage to contemporary Japanese painting. I highlight female portraits in a clean and graphic style. So, I would conclude with the idea that "Less is More"

Enquire here to request details of available works by Scott

-

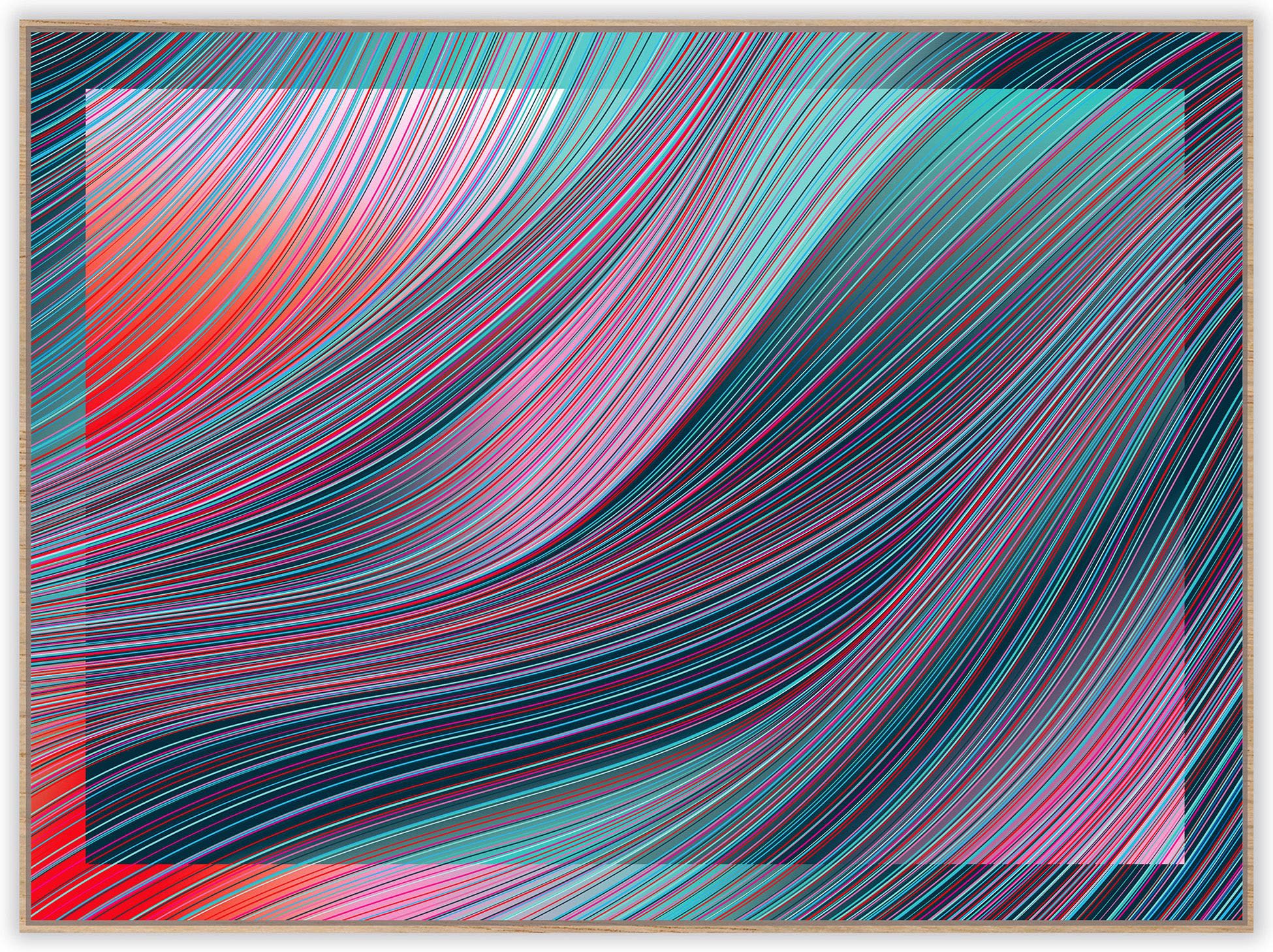

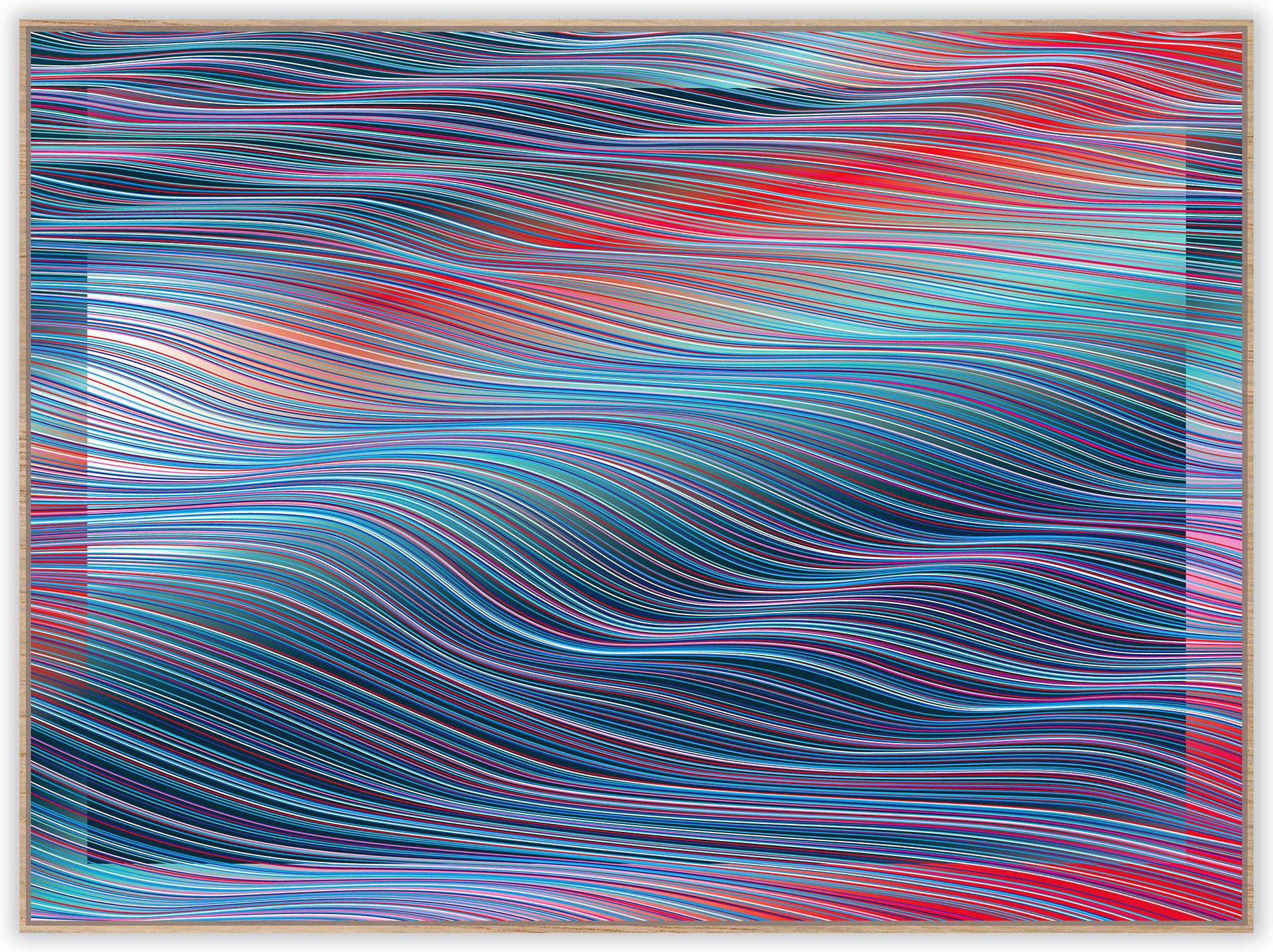

We met with Kai Clements who is behind the art of Kai & Sunny to take some time to immerse ourselves in the world of 'Elemental Mix'.

Please can you tell us the inspiration behind your new body of work 'Elemental Mix'?The inspiration for this new body of work focuses on how nature has the ability to change the way you feel. How we rely on nature for happiness in times of uncertainty. How you might feel when subjected to the force whilst surrounded by nature.

Can you describe the exhibition in 3 words?

Hypnotic - Calm - Kinetic

What inspires your colour choices for your artworks, and is there a specific focus on colour theory?

Colour is becoming more and more important in the paintings. The transition between colour is creating the movement and the mood. I like to use colours that compliment each other but mostly offset this with opposite colour usage i.e red and green. The colour combinations help the form and direction of the pieces and dictates the flow and energy. The colour combination also has the ability to interfere with the foreground and background and creates a sense of confusion.

How do you initially prepare for the composition of each piece?

Each painting starts with sketches to create the composition and over all shape. This is taken from observations around elements from nature. Once the piece is ready to paint I use bold painted layers behind working with colour gradients to create the flow and energy. The thinner lines are then applied on top to add to the movement and creates the over all mood of the painting.

How important is nature and our planet in the creation of your work?

Nature is the key element in the work but it’s the effect nature can have on us that is the interesting part. It’s about how nature can create positive energy and is important for our mental health.

How important is the collaboration between music and art in your work?

Working with Toydrum on the music for the show is such a positive element. Adding music enables you to go further and explore the energy and movement within the work. It enhances the experience.

Enquire here to request details of available works by Kai

-

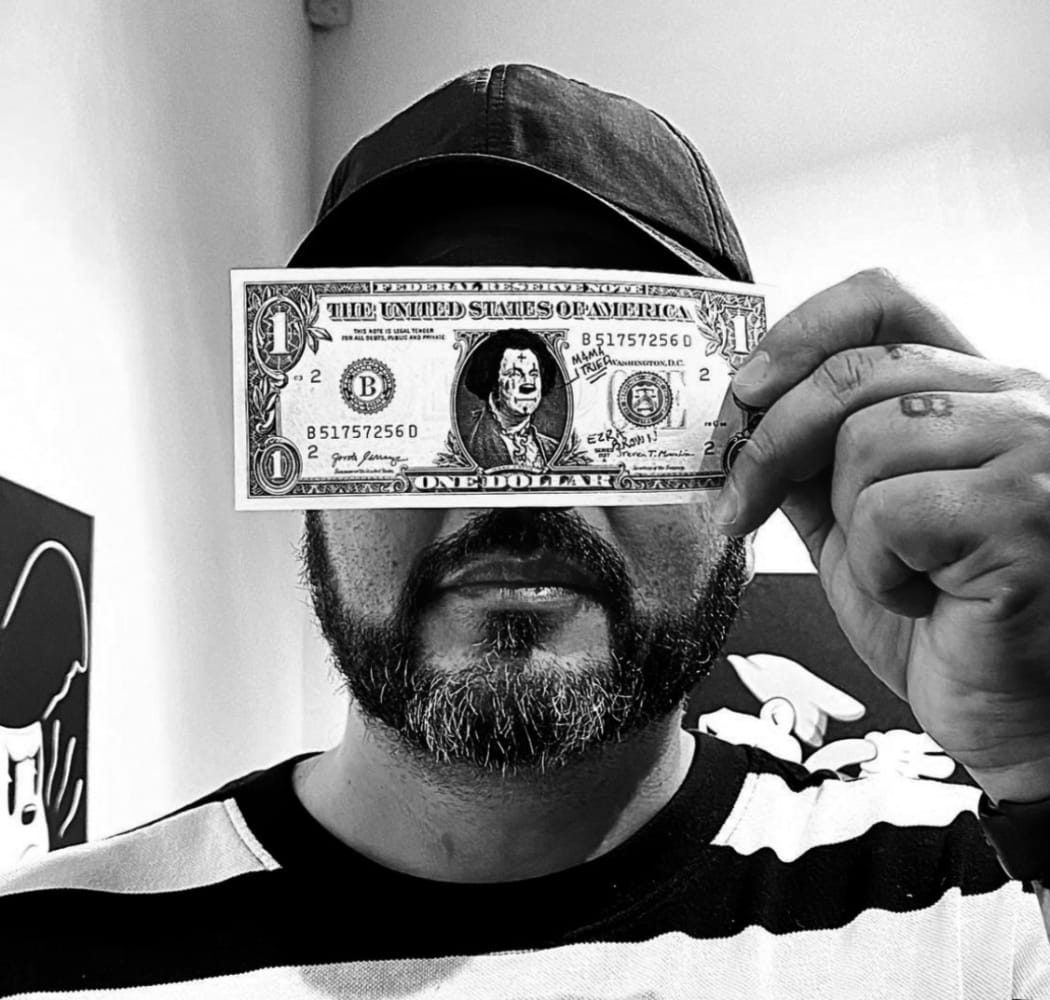

we sat down with Ezra over a pizza and fired over some questions to get to know him a little better!

Tell us about a bit about yourself and your background.

I grew up in East Los Angeles and I went to the Academy of Arts in San Francisco to study art.

When did you first discover your interest in art and creativity? Which artists would you say are your key influences?

I first found my love for art around the age of 5. The biggest influence in my career was my father. He was always drawing and painting around me and my brothers. So I naturally gravitated towards the arts.

Where do you find inspiration or what motivates you to create? Explain how to be happy!

The inspiration for all of my art comes from everyday life. I tend to draw from emotions we have all gone through at one point in time in our lives. My motivation comes from the passion and love I have for creativity.

Could you tell us about your artistic process and how you would describe your style?

My process for creating a piece of art is quite simple, I create what and how I'm feeling. If that doesn't work then I think of a past experience and build from there. The style I draw and paint in is called rubber hose. It's a style that became popular in the 1920's. I've always loved artwork from that era, especially the cartoons.

In your solo show ‘I Used To Be Happy’, you paint a character ‘Happy The Clown’. What's the purpose or goal of portraying this character in your work?

Happy is a character loosely based on me and my emotions. I'm not good with wordsnor at expressing myself and especially when it comes to my mental health. That's why I felt it was easier to come up with a character to help my cope with my emotions. It was easier for me to paint and draw something than to write it down. I just didn't know it was going to have such a positive impact on people as it did. I've had people from all walks of life message me thanking me for creating artwork that was speaking on what they are going through.What are your future plans as an artist?

My plans for the future are to eventually have a larger platform to keep on creating and hopefully work with organizations to help make mental health awareness something everyone feels comfortable talking about. I would also love to continue to show my work overseas and connect with people from all over the world and share the love I have for art.